Philosophers try to organize our thinking about different issues. They make lots of distinctions, as part of clarifying and analyzing concepts. If someone proposes a definition, then may offer counter-examples to it.

They give arguments. They respond to objections to the arguments they like, and evaluate and criticize or try to figure out what’s wrong with other people’s arguments. They try to unearth hidden assumptions in their opponents’ arguments. They try to show that their opponents’ views are inconsistent or lead to absurd results.

All of these activities are part of a kind of critical thinking that philosophers engage in. We can call it the philosophical method.

You already engage in many of these activities yourself in day-to-day interactions. Suppose you and your roommate normally each wash your own dishes, but agree to rotate who washes up after you jointly host guests. Now you’re arguing about whose turn it is:

I did it last, it’s your turn!

No, my turn came last, on Monday.

Perhaps this is just a disagreement about the historical facts, that we can settle by producing a photo from Monday night, or remembering that guests also came over on Tuesday. But what if instead you continue:

On Monday we had pizza delivered, so there were no dishes. So it’s still your turn.

No, Monday was my turn — it wasn’t my decision to order pizza!

Here you and your roommate are arguing about what counts as complying with your agreement. You may not have explicitly formulated how the agreement applies to this kind of case.

As your argument evolves, perhaps you start discussing who’s contributing more to the household. Maybe you put in more time, but your roommate puts in more money. How should these contributions be weighed against each other? (Should twice the time count more than twice the money?)

These disputes will use some of the same argumentative and investigative tools that philosophers do. There can also be less mundane examples, where the answers have more serious practical import: Given that such-and-such happened, does that count as inciting violence?

The philosophical method can also be applied to some questions that science engages with. Philosophers don’t usually themselves go around running experiments or digging in pyramids. Their method doesn’t involve empirical research of those sorts. It instead requires one to think and reason carefully. But those are things that scientists aim to do too, when trying to interpret their experimental results, or understand their consequences. Philosophers can and do engage with scientists in performing these activities.

So the philosopher’s tools can be employed in everyday inquiries and disputes, and also in some scientific contexts. What makes the philosophical method distinctive is that it can also be used in further ways, too, where our everyday and scientific methods make no progress. The philosophical method can be used to address fundamental questions, like:

The way I would explain what philosophy is, is that it’s the use of the kind of critical thinking we described to seek answers to such fundamental questions, and to critically examine important beliefs that we normally take for granted.

In our introductory philosophy courses, we’ll be doing this:

Socrates famously said The unexamined life is not worth living.

I don’t agree. I don’t think a life has to be worthless, or incomplete, because it lacks philosophical reflection. But since you’re here, I take it that you’re curious about the kinds of thinking that philosophers do, and how to make progress with the questions philosophers address. So at least for the duration of this course, you’ll be trying on the philosopher’s boots and learning how to walk in them. Then you can better understand what they’re up to, and decide for yourself what value this activity has.

Sometimes students have expressed disappointment that they’d only be learning intellectual tools in our courses, and not learning answers to the big questions we engage with.

But suppose I knew the answers to some of these questions. Or at least thought I did — maybe I’m overconfident? Let’s suppose in some case I’m right, I really do know the correct answer to some interesting and important philosophical question. Of course, there will still be philosophers who disagree with me. They’re not thinking the issues through correctly. If you gave me enough time with them — we didn’t have to worry about paying bills, doing dishes, pride, impatience, or other practical nuisances — then maybe I could explain matters clearly enough to get them to see that they’re wrong, and what mistake they’re making. Or maybe not. It’s a lot harder to satisfyingly explain to someone why they’re wrong about something, than it is merely to know that they’re wrong.

Suppose you’re interested in the philosophical question that I happen to know the answer to, so I tell you what the answer is. But my counterpart comes along and tells you something else is the answer. My counterpart may be sincere: he just hasn’t thought the issue through as successfully as I have. Or maybe he’s saying what he does because you accepting his answer will help a secret agenda.

In any event, how are you going to know what to think? I’m not necessarily going to be the more charismatic one. Or he may know much more than me about some other topics, and so be more impressive. Just hearing the two of us give our answers, and even speak on their behalf, is not guaranteed to help you know for yourself what the right answer is. You have to also learn how to evaluate the reasons and arguments we think support our answers. In other words, you have to engage in the same critical methods we do.

Of course, answering the major questions philosophers are interested in is like sending a manned mission to Mars. It’s complex and takes a lot of preparation. There’s only so far you’ll be able to get, in a single semester. But you will learn to make a few steps, and you will make important progress.

Some forms of learning are ones where you can start with basic foundations, then proceed to the next layer in an organized way. Like building a house. Foreign languages are often taught like this in school.

Other forms of learning are ones where you’re thrown into the middle of things, and have to stay afloat by whatever means available. Learning a foreign language by immersion is more like this.

Your philosophical education — whether it consists of one course or twenty — will be more on the second model. This is not because being a novice makes you unready for the foundations. It’s because of the nature of philosophy.

Some philosophers have built up systems starting with basic principles and claims about fundamental truths. They expected their readers to agree with those obvious starting points — at least after a little careful thinking. They then put enormous intellectual work into carefully organized systems balanced atop those starting points. What happens then is their audiences mainly raise doubts about those supposedly unquestionable starting points.

In philosophy, there’s hardly anything that’s really immune to questioning. And the more supporting weight you want some assumption to bear, the more ways philosophers will find to challenge it.

So philosophy isn’t like building a house. It’s more like working on a crossword puzzle. You’ve got to try certain combinations out, a little bit at a time. Sometimes you might pencil some answers down, that in fact don’t really work, and you won’t be able to see that until much later. But that’s the only way to solve a serious crossword puzzle. You can’t try to do it all at once. You won’t get anywhere.

Philosophy is like that. Any place you choose to start will be subject to some controversy and dispute. Since you’re just starting out, it’s true you often won’t yet be ready to understand and grapple with many of these. But even the philosophy experts have to start somewhere. We also have to make do with plausible assumptions and initial hypotheses, and sometimes only being able to roughly approximate the truth. Let’s just make sure we stay ready to come back and re-examine those starting points, and revise or improve or defend them later, depending on what then seems to make most sense.

As we said before, the arguments you consider in this course (and elsewhere in philosophy) usually won’t be absolutely decisive. (They’ll mostly be deductive arguments, but they won’t have premises that are beyond intelligible doubt.) We won’t deal with obviously bad arguments (except to learn an occasional lesson). The arguments we consider seriously will at least have some reasonable plausibility. But just because we consider an argument in class, doesn’t mean it has no shortcomings, or that there’s nothing its targets can say in response.

Similarly, some of you will suggest objections to arguments we consider in class, and I will sometimes say, That’s a good objection.

I usually won’t mean your objection must be fatal to the argument. Maybe the argument can be fixed up in some way to work

around it. I’ll just mean your objection also has some plausibility, and that it raises difficulties that the argument’s defenders should try to answer.

In philosophy, you can’t support a position simply by pointing out that someone you’ve read holds it, or that it’s very popular. Those might be good reasons to consider a view. You could then go on to explain why you think Philosopher X’s arguments for the view are persuasive, or to criticize those arguments — but a mere statement that the renowned Professor X holds a certain position carries no argumentative weight of its own. Similarly for a mere statement that so-and-so many people accept the position.

Sometimes people don’t even appeal to authorities, and will just argue like this:

[BAD] P has not been shown to be false. So it must be true.

If no positive support is already in place for claim P, then reasoning of that sort is fallacious and wholly unconvincing.

But there are argumentative moves in the neighborhood that are importantly different, and that can be more reasonable.

If P is a claim that seems intuitively to many of us to be true, or for some other reason in our dispute or investigation there is some presumption that P is true, then anyone who seeks to prove not-P bears what we call the burden of proof. If she doesn’t succeed in proving not-P — if we can show that her arguments that not-P are no good — then we’re entitled to continue accepting P.

In such a case, we’re legitimately reasoning as follows:

[OK] We start with some presumption that P is true. And P has not been shown to be false. So we can reasonably continue to accept P.

Of course, this isn’t any conclusive proof that P. There may be some reason why P is in fact false — we just haven’t come across it or appreciated it yet.

Here’s an example of this kind of situation:

We may be in no position to decisively prove that Thatcher wasn’t a terrorist. But given what we know, it’s very unlikely that she was. At present, it’s reasonable to presume she wasn’t. And until a convincing argument that she was a terrorist turns up, it’s reasonable to continue presuming that. The burden of proof is on the person who wants to persuade us that Thatcher was a terrorist.

Philosophers often seek to establish that it’s their opponents, and not they themselves, who bear the burden of proof.

Where the burden of proof lies will sometimes depend on the “dialectical situation,” that is, on the kind of debate the parties are having. For example, contrast these two situations:

Here Erika has the burden of proof. Matt only needs to examine and criticize Erika’s arguments. He is not obliged to argue that God does not exist.

Here both philosophers have the burden of establishing their position.

Sometimes we’ll be in dialectical situations where we’re not able to give compelling arguments that P is true, nor able to give compelling arguments that P is false. At least it will be valuable to know that’s the situation we’re in. We don’t want to overestimate how good or bad the case for P is. With luck, as our inquiry continues, we might later come upon stronger reasons in support of one side over the other.

Here’s a common argument against the death penalty. Suppose Lefty argues:

Imposing the death penalty for murder is hypocritical and inconsistent. You only punish people for murder because you believe killing to be wrong. But then the death penalty itself must be wrong, because it too involves killing someone. And two wrongs don’t make a right. Imposing the death penalty is just as bad as killing someone in cold blood.

Lefty is trying to convince us that we have to take the same view of murder and of capital punishment, else we’re being inconsistent.

Now suppose Righty comes along, and criticizes Lefty’s argument as follows. (Credit here to my former colleague Tim Maudlin.)

You say capital punishment is supposed to be analogous to murder. Well, then, you should also count other activities committed by the state as analogous to those same activities when committed by criminals. In particular, since kidnapping — confining someone against their will — is wrong when committed by criminals, so too must it be wrong for the state to confine people against their will (in jails). Hence, if your argument that capital punishment is inconsistent were successful, then by the same reasoning, it would also be inconsistent to jail kidnappers. That is clearly an unacceptable result. So there must be something wrong with your analogy. True, murder and capital punishment are similar in some respects. But there are also important differences between them. And these differences seem to matter to morality.

Of course, Righty hasn’t established here that the death penalty is morally acceptable; he’s only criticized Lefty’s argument that the death penalty is unacceptable. There might be other arguments against the death penalty, which are better than Lefty’s.

In this exchange, we’ve seen an example of shifting the burden of proof. Lefty pointed out an analogy between murder and capital punishment and urged that they be regarded similarly. This puts the burden of proof on Righty, who wishes to regard the cases differently: Righty has to find some disanalogy, or to argue that the cases aren’t genuinely analogous.

In our exchange, Righty argues that if Lefty’s analogy were good, then so too should a second analogy be good, but the second analogy leads to clearly absurd results. So Righty concludes that the original analogy must be bad too.

This shifts the burden of proof back on Lefty, who has to argue that the cases really are analogous after all.

Arguments by analogy often exemplify such shifts in the burden of proof, because they are hostage to unnoticed or unacknowledged disanalogies.

It can be legitimate to criticize a philosopher by saying, Look, you seem to be giving such-and-such an argument, but that’s not a good argument, because…

Maybe the philosopher did not mean to be offering the argument you’re discussing, after all. It can still be instructive and philosophically important to learn that the argument they seemed to you to be giving is not a good one.

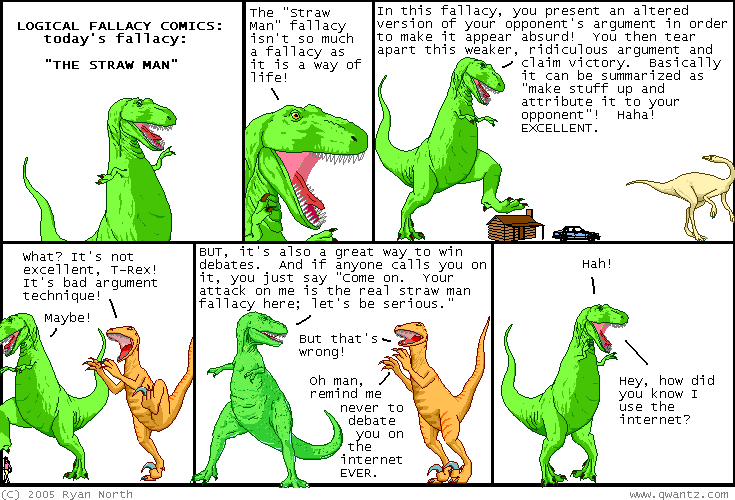

But we shouldn’t abuse this lesson. We shouldn’t just attribute stupid arguments to our opponents and then criticize those stupid arguments. That is called attacking a straw man.

Here’s an example:

A: In the end, affirmative action has harmful effects on society and so it should be abandoned.

B: So what you’re saying is that all the jobs should go to rich white guys?

That is not what A said, and it doesn’t advance the debate for B to misrepresent A’s view in that way. Of course, B may think that the more careful view A really advanced will have that consequence — but then B’s strongest case would be made by presenting their reasons for thinking so, rather than seeming to just twist A’s words.

We should exercise “charity” when interpreting our opponent’s arguments. That is, we should try to understand them in the strongest versions we can — even if that requires helping the original authors out in some ways. It’s of little value to “score points” against a weaker version of their argument, if we know there’s an improved version they could turn around and respond with. We can help our own view the most by engaging with and responding to the strongest arguments we know the other side can give.

Here’s another example of being incharitable:

C: We should have mandatory military service. People find it inconvenient, but they should realize there are more important things than convenience.

Whether you support or oppose mandatory military service, you should realize there are better/stronger arguments against it than merely its being inconvenient.

This page tried to explain, and enable you to understand, the following concepts: